Last night, I saw The Boy and the Heron during its Thursday night preview release with Davis, my partner in life and a contributor to this very site. We had seen it at this year’s New York Film Festival – yes, we’re quite fancy and very cool – and we were excited about the English dub, which features Christian Bale, Dave Bautista, Gemma Chan, Florence Pugh, and many others, but most notably Robert Pattinson in his voice-acting debut. With the Japanese and English versions under our belt, we would be the ultimate Boy and the Heron viewers on Day One of its official release.

But despite publicizing the English dub, the theater that we attended only had the Japanese subtitled version – and they wouldn’t have the dub until Monday. We watched the movie again, of course, because we both loved it the first time we saw it; and I’m glad we stayed, because the first time watching it was fantastic. The second time was transcendent, and I truly believe it was because revisiting a film tends to get me thinking about what I didn’t notice the first time – details, themes, messaging, and more that might have gotten lost when I was initially letting it wash over me.

Before, during, and after our viewing experience, Davis and I talked about The Boy and the Heron in-depth, comparing ideas and interpretations. What follows is a combined investigation into both our thought processes about Miyazaki’s masterpiece, with Davis’ full permission.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/The-Boy-and-the-Heron-081823-09-fc1971f1f0824b9d8914c11488b9415b.jpg)

And it is a masterpiece. It took at least two viewings for it to fully sink in what The Boy and the Heron means to me, and it’s especially prevalent given that both Davis and I watched every single film Studio Ghibli ever released within the span of this year. His latest is a culmination of the ideas and thematic resonance Hayao Miyazaki has worked into his stories for decades, but I’ll get there soon enough – first, I should note why it was so exciting to see this movie finally debut.

Davis has recently gotten deep into animation as a medium, and he found a small obsession within the realm of anime – that is to say, animated films produced by Japanese studios. The most famous (and popular in the United States and Europe) come from Studio Ghibli, which was established in 1985 by four men, among them future animation legend Miyazaki. I grew up with Ghibli movies, primarily classics like Spirited Away, My Neighbor Totoro, and Howl’s Moving Castle. They were formative to my appreciation for animation and film in general, and can’t imagine my early film experience without them.

Thus, as soon as its release was announced, The Boy and the Heron became my most anticipated movie of the year. After all, this is Miyazaki’s first theatrical film released after I started taking an intense interest in movies and pop culture, but also his first since I’ve been allowed to see PG-13 movies. Lest we forget, his latest feature was The Wind Rises in 2013, and that was intended to be his last – even before its release, he announced his retirement. He supposedly reversed his decision after working on a short film in 2018 for the Ghibli Museum, but it’s worth mentioning that nearly every time he reverses his public decision to retire, it’s after his son Goro Miyazaki made films for Studio Ghibli that aren’t as well-received as his father’s are; Goro’s Earwig and the Witch, the first 3D animated Ghibli feature, was harshly panned by critics and audiences alike, and thus, Hayao must come out of retirement once again to show his son how it’s done.

(Of course, it’s probably a coincidence – but I like thinking that Miyazaki intensely scratches his head every time Goro releases a new film, trying to get rid of a migraine that will inevitably grow into a bout of creative inspiration)

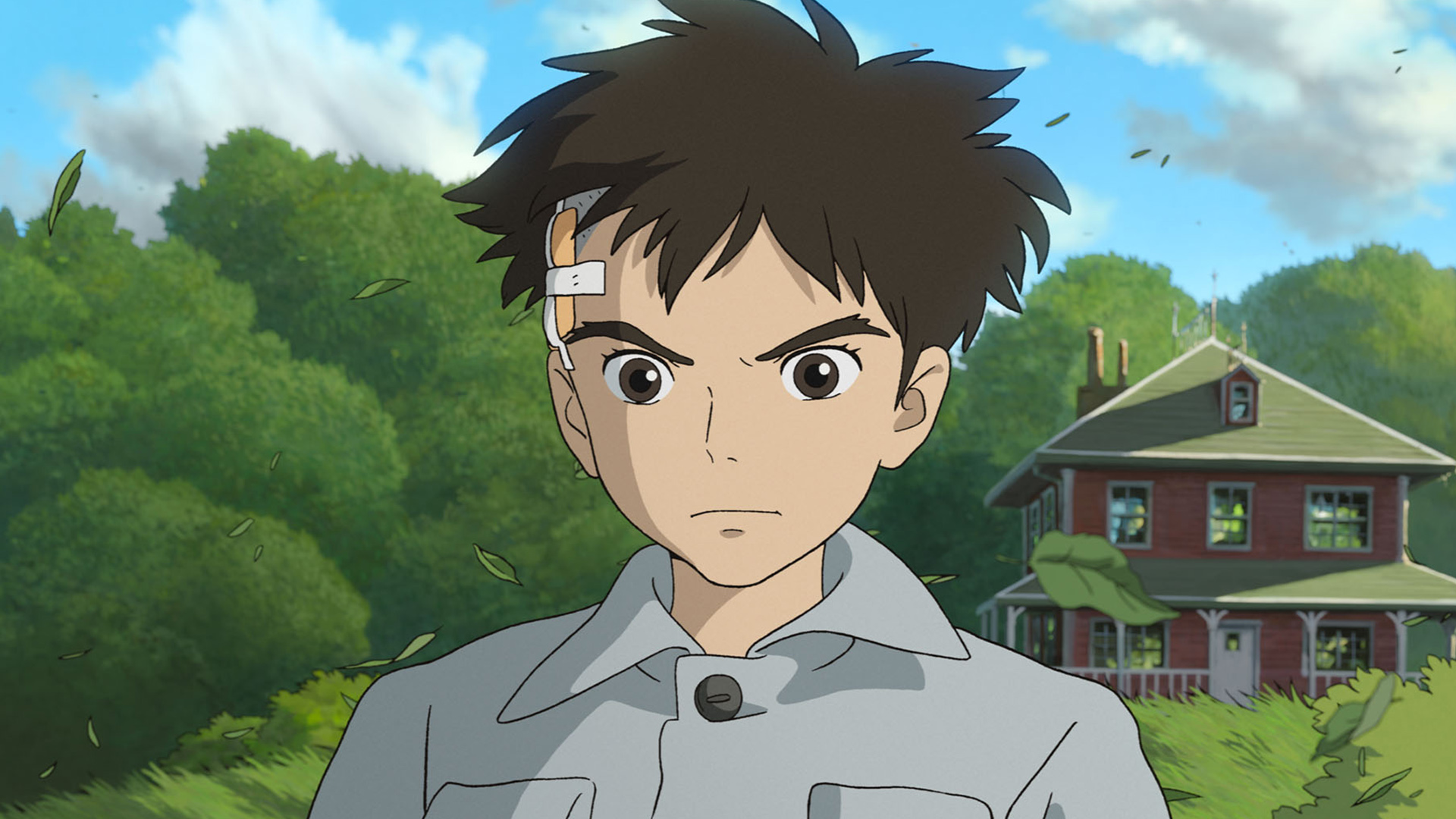

The Boy and the Heron is Miyazaki’s first film in ten years, announced in 2016 and meticulously created in Studio Ghibli’s signature 2D style over seven years. It’s loosely inspired by Miyazaki’s experience reading the 20th-century novel How Do You Live? – not the novel’s story itself, which is a common misconception given that the film’s Japanese title is the same as the novel – but it’s an entirely original story, and as magical and perfect as we’ve come to expect from the master.

It feels like these days when big-name filmmakers come out of retirement to make “one final film,” or finally make their “magnum opus,” those terms and phrases are used as marketing tactics to artificially craft even more hype for a major release. It may not be abundantly clear when it comes to The Boy and the Heron, but it’s no mere tactic when it comes to Hayao Miyazaki. Just when you think he’s done his greatest work, he comes back with an emotional gut punch for the ages.

My excitement didn’t just stem from the fact that Miyazaki is a visionary who has a stark skill with the art of storytelling. Even the least interesting Studio Ghibli productions — bar Earwig and the Witch and Ocean Waves — are simply delightful, creating worlds that are easy and pleasant to immerse yourself in. Even Grave of the Fireflies, a dour tale about starving World War II civilians in Japan, paints an effective portrait of perseverance and heart. If nothing else, it’s about humanity, and The Boy and the Heron continues that trend effortlessly.

There will always be a very special place in my heart for Spirited Away. It’s still my favorite Ghibli film, and I suspect it always will be. It’s classic upon classic, and watching it as an adult has opened my eyes to what it means to me now, as opposed to when I was a more impressionable child – but this is not a review of Spirited Away. That film, and most of Miyazaki’s others, are key to a deeper appreciation for The Boy and the Heron, especially when you see how far he’s come as a storyteller.

In the complete picture that is the Ghibli pantheon, The Boy and the Heron is a culmination of Miyazaki’s works and the themes that have proliferated each one. It’s Spirited Away in tone meets The Wind Rises in setting, and you can tell this is a story that means a lot to its creator – after all, the emotion is pure and genuine, propelled by characters whose lives you buy into through the sheer virtue of their existence. He cares, so we care.

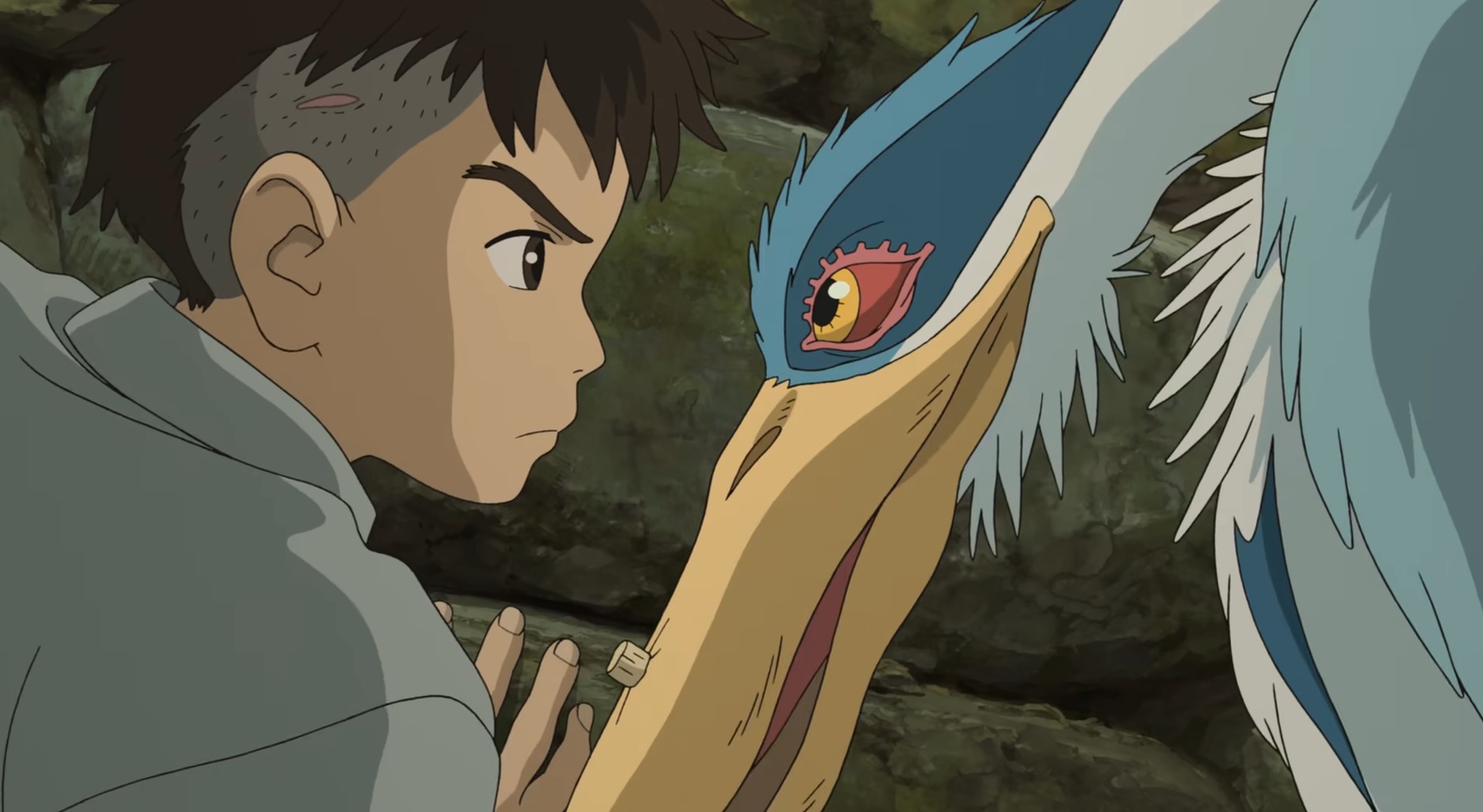

Not enough people are giving the film credit for how funny it is. Miyazaki is no stranger to comedy – Porco Rosso and Ponyo come to mind, though both are from very different sides of the Ghibli spectrum – and though The Boy and the Heron often tackles darker subject matter (it’s PG-13, as opposed to the standard Ghibli PG rating), it has its goofiness, cuteness, and wholesome, heartwarming moments, all in the name of connection and showing the central character, Mahito, the many faces our world (and others) can have.

Both Davis and I are confident that there is nothing more concrete about The Boy and the Heron than the simple fact that it is the very pinnacle of Miyazaki’s worldview. Bits and pieces of his idealogy have permeated his other works, but in The Boy and the Heron, he spells out very clearly that he believes the world is evil and cruel, but individual people have the intrinsic capacity for love. No matter how bad that world is, the best thing you can do is love the people and beings around you, and that’s beautiful in and of itself. Every living thing deserves that same love and respect, and that’s the only way you can have a good existence in a terrible world.

You can tell this is a movie made by a man with some lived experience.

It doesn’t matter which version of The Boy and the Heron you end up seeing. I’m excited to see the English dub at some point, but I’m not itching for it in the same way I was before my second viewing. Many of the questions I had the first time around – why is there a little bald trickster inside the gray heron? Where did Kiriko originally come from? How did the parakeets evolve into cannibalistic monsters but the pelicans stayed the same size? How did this mysterious other world come into being in the first place? – didn’t end up mattering, and I found I didn’t even care by the end. My investment outweighed my need to know, and that’s the magic of Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli – they create worlds that wash over you like a warm bath, where the involvement is enough, and you’re just happy to be there.

I’m glad we live in a world where such beautiful art can be created, and I’m glad we’re alive to appreciate it.

Leave a comment