Welcome to class! My full-time job is working at a university, and I teach as well. One of my dreams has always been to teach a film class. Taking students through the world of cinema and helping them learn about the art form that I am so passionate about would be an amazing experience. But alas…I teach math. This series, “Lessons from the Wasteland,” is my opportunity to offer readers a curated watchlist to learn through doing (…watching movies). Each film on this list will highlight a filmmaker, sub-genre, filmmaking technique, or significant topic in order to broaden your cinematic horizons. For this month, we have…

Close-Ups

The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928)

In utilizing a close-up shot, a filmmaker can put the emotion of a scene into the hands of the actors. Cameras at the dawn of cinema were clunky and largely stationary. When you watch early films, you will notice that there are not many camera movements and everything needed to be accomplished in-camera. Wide shots were the standard, and you would see everything playing out in front of you. But with The Passion of Joan of Arc, director Carl Theodor Dreyer leaned heavily into the more dynamic shots of close-ups.

The film is about the 1431 trial of Jeanne d’Arc for heresy, and we need to feel the turmoil raging inside of her as she is met with illogical and biased treatment in the eyes of the law and God. Luckily, Dreyer had an incredible performer in Maria Falconetti to sell this horrible tale of injustice and judgment. Dreyer’s film looks incredibly modern compared to so many of its peers because it has so many shots that are seen often today, but were certainly not as frequently seen back in 1928.

The Passion of Joan of Arc is not the first film to utilize close-ups, but Dreyer leveraged them to maximum effect. The camera lingers on Falconetti’s face as she expresses such a wide range of emotions. You can see the frustration as she is met with biased and cruel interrogations from ecclesiastical jurists. You feel the fear and sadness that overcomes her as she begins to realize the fate that will soon befall her. But it is not just the facial expressions but the physical movement and placement of her head that speak to her state of being. She’s often chin-up and defiant, which feels so powerful thanks to Falconetti’s confident performance. At others, her head is dropped in defeat at the hands of these terrible men.

Dreyer even leverages the close-ups to present the jurists. Many of those shots frame these men in grotesque and unflattering ways to reinforce the distorted perspective being forced down upon Jeanne d’Arc. Dreyer even delivers some impressive shots that play around with high and low angles that accentuate the distorted world crashing down upon our protagonist. If you have never seen The Passion of Joan of Arc, you are missing out on such a dynamic and engaging masterpiece of early cinema.

Casablanca (1943)

Numerous shots throughout the history of film have stood the test of time and become fixtures in the lexicon of cinema. These shots have transcended their films, and many have become synonymous with their legacy. Some of these shots are complex and show off the impressive reach of what film can accomplish. Others are so simple yet hit so deeply on a human level that they resonate and last with us. That is certainly the case with one specific shot from the all time classic of Old Hollywood, Casablanca.

For so many, this classic period drama is one of the greatest films of all time. The romance at the core of the film is one of the most iconic ever put to screen. Humphrey Bogart’s Rick Blaine is a rugged individual who turns a blind eye in a tumultuous world, which is framed through his long, cynical lens. Ingrid Bergman’s Ilsa Lund is a woman stuck between a man she loved (and still loves) in Rick and an important man trying to make a difference in the world. Victor Laszlo (Paul Henreid) is that important man, on the run from the Nazis during WWII. When Ilsa and Victor arrive in Casablanca and, in turn, back into Rick’s life, the world of Rick’s far-off bar gets turned upside down.

There is plenty of tension throughout the film between Rick and Ilsa. Will she continue her mission and leave with her rebellious lover? Or will she give in to her feelings and stay with the man she loved, who has now shunned the world around him? This is a compelling and engrossing dynamic that leads the audience all the way up to its climax at the airstrip. Isla has her choice in front of her, and Rick makes it clear that her place must be with Laszlo (at the sacrifice of his own happiness). That is when one of the most moving and beautiful shots in film occurs. Director Michael Curtiz has the camera linger on the beautiful face of Bergman as a single tear begins to caress her cheek. The overwhelming emotions Isla is navigating in this moment are distilled in that single tear that hangs on her face as the audience is forced into an intimate space with her. Bergman acts this scene so perfectly, and she flaunts vulnerability in this iconic and beautiful shot.

The whole love triangle of the film is embodied in this single shot, her reaction. Curtiz and Bergman show just how powerful a single shot can be, and it’s undoubtedly one of the greatest shots in one of the greatest films ever made.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966) / Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

We might have to cheat a little bit with this month’s article. It is a struggle every month to distill such significant aspects, genres, and figures in film down to five simple examples. But these next two entries feel naturally paired the way they are, as each entry is from a singular creator who leverages close-ups to such poignant and palpable effect.

Sergio Leone is one of the greatest filmmakers to ever do it, yet he has only a few films to show for it. His career came to an end when he could no longer stomach the restrictions of the filmmaking industry crashing in around him, making his grand American epic, Once Upon a Time in America. But this gangster film was not the trademark of his great career…the Western was. Two of the greatest Westerns of all time came from Leone’s creative mind and were brought to life in epic proportions. But just because the runtimes are huge and the scales are vast, Leone is one of the greatest at leveraging close-ups to magnetic effect.

Eyes. That is all you need to tell a story. Two of the greatest shootouts in the history of film come to life on screen with all of Leone’s masterful touch. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly features an iconic stand-off between the titular trio. The music is epic. The tension is heightened. The filmmaking is superb. The camera slowly gets closer to its subjects, and the editing quickens as well. The close-ups of eyes and guns are all you need. The titular “Good” is Clint Eastwood’s Blondie, whose eyes remained squinted and steely in that classic Eastwood way. He fixates on Lee Van Cleef’s Angel Eyes (the “Bad”). He shifts focus from Blondie to Eli Wallach’s Tuco (the “Ugly”) with great suspicion as his cool demeanor begins to wane with each edit. Tuco’s paranoid eyes look like they are about to pop out of his head. Their hands all represent their state of mind, with Eastwood’s steadiness standing out compared to the trembling Wallach’s and the nervous Van Cleef’s. This standoff turned shootout is one of the most tense sequences ever put to film, and Leone’s leveraging of close-ups ups the tension with every new cut. The way he is able to capture character in those moments is profound, with each shot gorgeously and meticulously framed. This is cinema at its most powerful.

Leone channels that same energy in the portrayal of his characters in his other Western epic, Once Upon a Time in the West. There is a standoff between our protagonist, Harmonica (Charles Bronson), and the antagonist, Frank (Henry Fonda). The way that Leone leverages close-ups for this final confrontation is incredible. The camera lingers on Harmonica’s eyes and cuts to a much younger version of the character. Through this powerful bit of filmmaking, we learn that Harmonica has great motivation for seeking out the dangerous and dastardly Frank. The way that Leone captures Bronson’s face is so powerful that you can feel the rage, intensity, and focus in his eyes as they stare down the camera as well as Frank. With Frank, there is another layer of power to these close-ups. Fonda was a heroic figure in the world of cinema, and his taking on this villainous role was a shock. Leone wanted to highlight Fonda’s piercing blue eyes, and those close-ups crackle with intensity. Leone used these close-ups so perfectly to accentuate the features, demeanors, and emotions of his characters. Overall, less dialogue and a greater focus on visual storytelling made Leone one of the greatest to explore the cinematic medium.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) / A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Stanley Kubrick is one of the most renowned and controversial figures in the history of cinema. His filmography was light for a career that lasted from the ’60s to the ’90s, but so many of his works stand as masterworks of the art form. His verbally abusive behavior on set certainly made him infamous, but the final products of his creativity made him one of the greatest filmmakers of all time. Kubrick obviously had no problem challenging his actors in twisted ways, and that certainly carried over to his dynamic with his audience. He created some of the darkest and most dangerous characters in all of film over the course of his career, and he made sure that his audience could neither run nor hide from them.

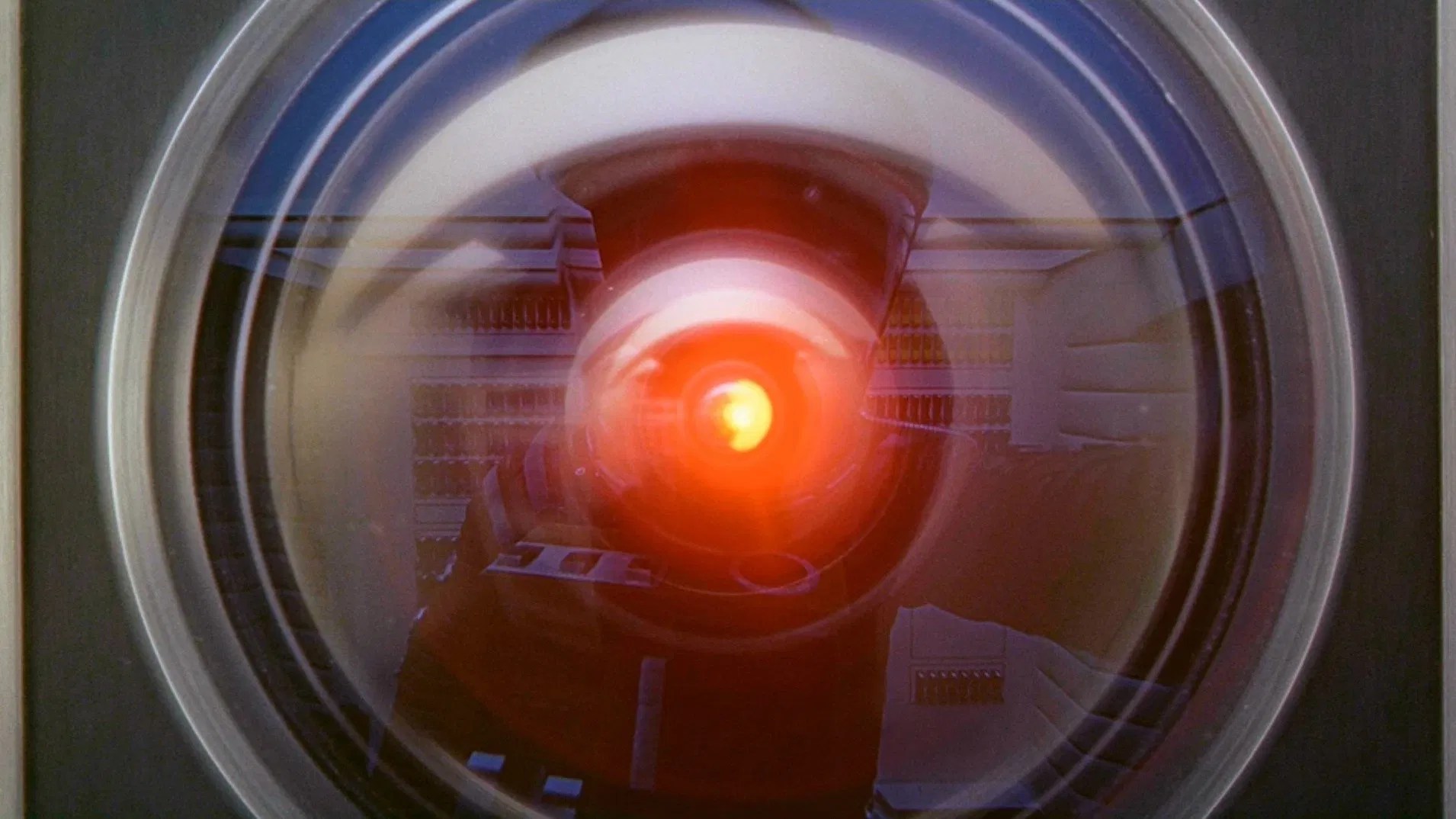

A great example of this discomfort is present in 2001: A Space Odyssey. When we think close-up, usually we think of an actor with a close shot of some aspect of their body. In 2001, this antagonist is no human being…but they do have an eye. This eye is unblinking, everwatching, and expressionless. But Kubrick is able to imbue this eye with so much emotion and thought through the editing and context of the scene. However, you still need a powerful visual to project those emotions and thoughts onto. The radiating red light that is HAL-9000’s eye is iconic, unnerving, and powerful. Kubrick cuts back to this glowing eye when he needs to capture the powerful presence of this everwatching artificial intelligence. The camera holding close to this bright light is uncomfortable, and thus doubly impactful.

But Kubrick uses close-ups in 2001 for the opposite effect as well. Close-ups of the human characters reacting to the powerful presences in the film deliver just as much impact. Seeing Keir Dullea’s face lightened up by HAL’s gaze is powerful. Dullea staring down the visual wonders of the wormhole at the end of the film is also so powerful and terrifying. Kubrick strikes his audience down with awe and fear numerous times, and those shots still live on almost 60 years later.

But he did that again in a different way with A Clockwork Orange. This is not an emotionless killer AI; this is a demented and sick young man who is let loose into society. The shot of Alex DeLarge’s face in the milk bar at the beginning of the film is incredibly haunting. The way we see the camera look this haunting figure dead in the eyes is so unnerving. Alex feels soulless, and his eyes feel inhuman. There is a darkness behind the smirking gaze of Malcolm McDowell as that camera hangs on him. The head tilted down. The bowler hangs over his face. The fake eyelash accenting his one eye. There is something devilish and sinister inside this young man, and we can already tell thanks to this powerful introductory close-up shot.

We, the audience, are forced to gaze upon Alex throughout the film in many uncomfortable ways. He is getting tortured with that iconic eye contraption, and we are forced to be up close and personal to it. We witness Alex getting spat on for his horrific actions. We end where we began and realize that Alex never truly grew or changed despite all the trials he went through. That realization is the hardest to stomach, and Kubrick forces the audience to stare it right in the face.

The Sixth Sense (1999)

The close-up can also be a great tool for highlighting important narrative elements. The camera can be a guide for the audience to show us the true nature of the story or its subjects. A mystery can use a camera to navigate a space and highlight important elements or clues to the greater mystery. These shots can be clues or hints to allow us to explore what is truly going on in the film. A master of suspense, mystery, and twists, M. Night Shyamalan has used the close-up on so many occasions to accentuate the story (and specifically the twists) in his films. One great example is in his breakout film, The Sixth Sense.

There are plenty of great close-ups for emotionally driven character moments throughout; there is no denying that. But the most important close-ups do great service to the narrative as a whole, as well as improving the efficacy of the impressive twists. Symbolism is so essential to the effectiveness and depth of The Sixth Sense, as red and green are used to express the supernatural elements of the story (which give way to the final and emotional revelation at the end of the film). You will have a close-up shot of a red doorknob that strategically obscures the other evidence around the knob. Shyamalan is like a cinematic magician who will distract and obscure while revealing the truth at the perfect time – all while preserving rewatch value. You see a close-up of the picture of Cole (Haley Joel Osment) and his mother, where she notices a strange light refraction next to them. This ethereal presence is significant to the journey that her son, Dr. Malcolm (Bruce Willis), and the audience embark upon. A close-up of a thermostat lowering signifies that a ghost will be coming. The close-up of the tape recording of one of Dr. Malcolm’s sessions, where you can hear ghosts, forces the audience to be stuck with this haunting moment. The impact of the close-up of Malcolm’s ring on the floor at the end hints at the shocking revelation that has become the film’s lasting cultural impact.

Also see: Metropolis, The Third Man, Persona, Apocalypse Now, The Shining, The Silence of the Lambs, The Blair Witch Project, In the Mood for Love

Leave a comment