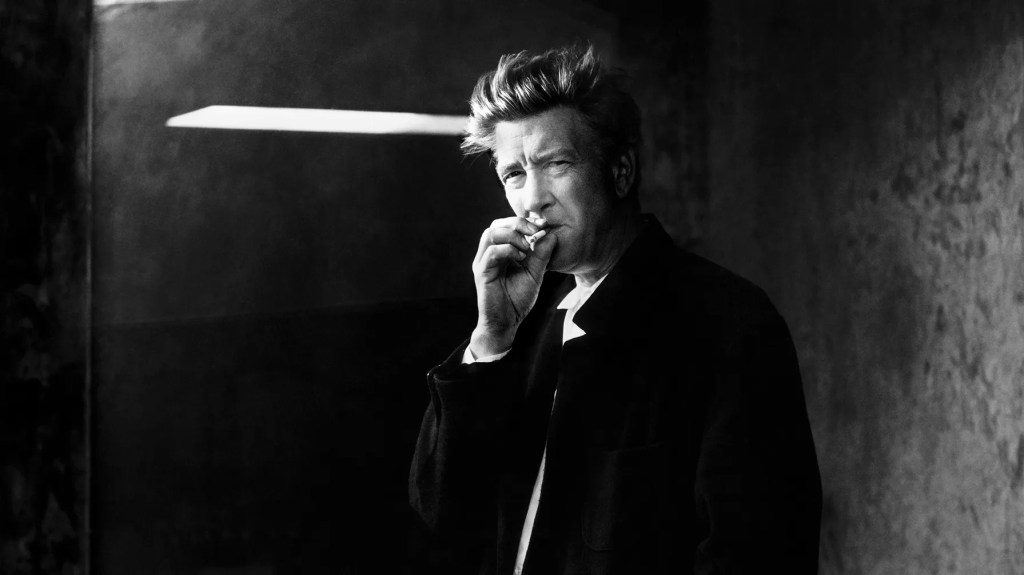

David Lynch, one of the most iconic and stylistically recognizable filmmakers of all time, passed away recently at the age of 78. Though his films were not always received with the critical and financial success they’ve been greeted with in the years since, as re-evaluations continue to place them on higher and higher pedestals, his influence across countless mediums is immeasurable – for proof, look no further than the adjective frequently used to describe his work and others, “Lynchian,” a word that, as far as we know, has no synonym. Many have tried to replicate his style, and not one succeeded.

There’s not much I can say that hasn’t already been said by the friends and collaborators that knew and loved him, but it’s difficult to articulate just how much his work has come to mean to me over this past year. I did not love all of his films, and I certainly did not connect with all of them emotionally, but, like many others, I continued to be spellbound by his wholly unique vision and worldly outlook that permeated every second of his films, series, and shorts. He was truly a singular creative mind, and in his honor, today I will be discussing and ranking each and every one of his directed features.

12. Dune

Lynch’s spectacular misfire was the first on-screen foray into Frank Herbert’s fantastical world of spice and prophets, and instantly retained immortality based on that qualifier alone. Though there’s a lot to roll your eyes at in Dune – stilted line deliveries, insulting archetypal portrayals, and enough exposition dumps to fill the Nile – it’s easier to look down on it when measuring it up against Denis Villeneuve’s blockbuster adaptations, both of which rank among my favorite films of all time. David Lynch’s Dune is laser-focused on its plot, and to a fault; there is virtually no character development or emotional stakes, sidelined (forgotten about?) in favor of economizing Herbert’s novel into one lean two-hour sci-fi flick that, yes, has remarkable practical effects and some appropriately loony performances, but falls short in almost every other area. This is notably Lynch’s first of many collaborations with Kyle MacLachlan, who would go on to play some of the director’s most iconic characters across more than three decades of film and television.

11. Eraserhead

In Heaven, everything is fine. Eraserhead, Lynch’s hyper-stylized, smothering nightmare of an odyssey about childcare, was his first feature, shot over four years before famously becoming a midnight movie sensation. Jack Nance, another frequent Lynch collaborator whose life was tragically cut short in the mid-1990s, stars as Henry Spencer, a mild-mannered, well-adjusted young man whose life begins to fall to pieces when he’s forced to care for his strangely mutated infant child. Love it or hate it, Eraserhead perfectly establishes Lynch’s bold and unapologetic tone, showing us a look into his weird and bizarre psyche that only his stories can give.

10. Inland Empire

A wildly unconventional three-hour surrealist drama with one of the most unorthodox production processes in the history of cinematic history, Inland Empire plays out like a painfully slow hodgepodge of ideas. Ostensibly, it’s about an actress (played by Lynch regular, Laura Dern) who loses her grip on reality after she’s cast in a remake of an unfinished, potentially cursed Polish film. There’s no straightforward narrative, and rightly so – after all, Lynch shot the film without a completed script – and so it acts more as a sensory experience, one that pulls together various ideas Lynch has about his experience in Hollywood and the entertainment industry…ironically, it’s made independently, outside of that very industry. He weaves in his bizarre web content (most notably, a series of shorts entitled Rabbits) that contributes everything and nothing, leaving it even more in the hands of the audience to determine what they will of the phenomena playing out before their eyes. At points, it can be interminable to sit through, but it’s worth noting that in a filmography full of risks and unfamiliarity, Inland Empire is Lynch’s most experimental film, a tone poem of discord and pain that encourages conversation and contemplation.

9. Wild at Heart

If there was ever any doubt that Lynch was strongly influenced by The Wizard of Oz, Sheryl Lee (who had already played the pivotal role of Laura Palmer on Twin Peaks) appears as Glinda the Good Witch at the conclusion of the already heavily-stylized Wild at Heart, which teams Laura Dern with a full-capacity Nicolas Cage in this violent, riotous, sexually-charged journey of the wills. Cage and Dern play Sailor Ripley and Lula Fortune, two young lovers who take the road after Lula’s overbearing mother (played by Dern’s real-life mother, Diane Ladd, who was nominated for an Oscar for her role here) sends a pack of criminals to hunt Sailor down. Controversially, Wild at Heart won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, which (depending on who you ask) denigrated its reputation or elevated it to the highest form of motion picture artistry. No matter how you might feel about the movie itself, it’s undeniable that Sailor Ripley is the quintessential Nicolas Cage performance. Seriously, if you look at the type of character that The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent, it’s a hodge-podge of Face/Off, Vampire’s Kiss, and (most importantly, I would say) Wild at Heart.

8. Blue Velvet

Lynch was known for his love of and investment in transcendental meditation practices, and because of that, I’d feel most comfortable calling each one of his works a “meditation” on a concurrent theme throughout his career, more so than I would most other directors. Blue Velvet, his (much smaller) follow-up to Dune, is a meditation on the inherent darkness of suburbia, an avenue that would lead many to believe that Lynch’s upbringing was as scarring and dangerous as Jeffrey Beaumont’s is in the film, and that’s simply not the truth. Even so, Lynch imbues the small town of Blue Velvet with an undeniable air of tension and mystery, leading Jeffrey (played by Kyle MacLachlan) to discover the seedy underbelly of the place he calls home after discovering a severed human ear in an empty field. Laura Dern made her debut here as Sandy Williams, Jeffrey’s more traditional love interest, while Isabella Rossellini stars as Dorothy Vallens, a nightclub singer who holds the secrets that Jeffrey needs in his search for answers – as well as serving as his more unconventional love interest. The cherry on top of it all is Dennis Hopper as Frank Booth, a sadistic gangster addicted to gaseous depressants. Lynch’s neo-noir techniques would later be refined in the next two films on the list, but much like his other films, Blue Velvet almost immediately took its place in cinematic history with its indelible imagery and disturbingly attractive veneer.

7. Mulholland Drive

This critically acclaimed nonlinear, highly unusual noir not only gave Lynch his final competitive Oscar nomination, but effectively bottled the bizarre feeling that a turbulent life in Los Angeles will give you. I only recently moved out to the City of Dreams, but already I can see the influence its beautiful, atonal dissonance had on Lynch’s unquiet mind – the LA depicted in Mulholland Drive (which has been the subject of countless theories and discussions since its release) is dreamlike, both harmonic and disharmonic, infinite but limited. At the center of its indescribable mystery is Betty (Naomi Watts), an aspiring actress who tries to help Rita (Laura Harring), a woman suffering from apparent amnesia. Mulholland Drive immediately gained a following, and became a massive cult hit despite its strange origin: Lynch originally developed the project as a TV pilot for ABC, and when it became abundantly clear there was no future, he bought the rights and expanded it into an R-rated barrage of sex, intrigue, violence, and unabashed wonderment. In a filmography full of iconic works, Mulholland Drive might just be his most well-known feature film.

6. Lost Highway

Lost Highway makes no narrative sense. This isn’t something new for David Lynch – in fact, he usually seems most comfortable in the abstract, playing in the realm of metaphor instead of linear structure – but Lost Highway feels different. A big reason for this is that, about two-thirds of the way through, Bill Pullman’s protagonist inexplicably shifts into a younger man, now played by Balthazar Getty, and the entire film shifts towards a brand-new trajectory. Themes and motifs repeat throughout both storylines (and come to a coda when Pullman returns near the end), but there’s a certainty and very strong intention threaded through the film’s seemingly disparate parts. At the center of it all is Patricia Arquette, playing two (but possibly one) character(s), and the chilling Mystery Man (played by Robert Blake, who would be arrested for murder five years after Lost Highway’s release). There’s a way to make sense of it, and even if it largely eluded me, Lost Highway is a compelling tone poem, the likes of which Lynch exceeds at.

5. Twin Peaks: The Missing Pieces

Our first foray into Twin Peaks, Lynch’s most culturally significant world, is The Missing Pieces, a feature-length assembly of deleted scenes from Fire Walk With Me (see: #3 on this list) that plays out as a companion piece, an addendum to the aforementioned prequel. In most cases, the reasons why these scenes and alternative takes were scrapped are self-evident (even if standard narrative flow is not always taken into account when it comes to Lynch’s tales), but I can’t help but notice that most of what was directly cut carries a much closer tone to the Twin Peaks series, which ran for two seasons on ABC – not appearing on this list, but its essence is represented by #5-3. These scenes are less dreary and more comforting, allowing us to see our favorite characters in their lives immediately before the series premiere. Several characters, including Jack Nance’s Pete and Joan Chen’s Josie, were cut entirely from Fire Walk With Me, and it was a lovely surprise to see them resurrected for The Missing Pieces. Perhaps they were cut from the film precisely because they didn’t align with the morose and downtrodden tone Lynch was crafting as a direct clash with the series, and in that case, I’m glad The Missing Pieces exists to preserve those moments in Twin Peaks history.

4. Twin Peaks: The Return

Mileage may vary on whether The Return is indeed a film, but as a quintessential part of Lynch’s filmography (and his last directorial effort), I’ve made the executive decision to allow it on this list. Like most of Twin Peaks’ eccentric strangeness, The Return is clearly not made to be understood in the conventional sense, and I came to find it’s more of an experience than perhaps anything else Lynch made. I appreciated the persistence and commitment to the show’s central theme — that evil endures, and where there is light, there will always be darkness. Through its shattering of conventionality, The Return becomes an interesting answer to expectations — in typical Lynch fashion, there is a pointed refusal to answer questions or resolve storylines, all while raising more to think about. It also appears to be an excuse for Lynch to showcase the bands and music he likes (the end credits of almost every episode contain an extended musical performance), and an opportunity to showcase one of the greatest ensembles ever assembled. The names in the guest cast are absolutely astounding (a whole host of “that guy!”s, in addition to a number of rising stars whose names have come to mean something entirely different in the years since). I have come to understand that this is a very important work of art for a lot of people, and I’m a bit disappointed I didn’t have the same enlightening experience that many have had. Still, when it comes to quintessential Lynch, there’s no question that Twin Peaks: The Return is an incredibly valuable part of the canon, and a fascinating experience on top of everything else.

3. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me

Fire Walk With Me is everything but tonally in line with the series that inspired it. Instead of following in the show’s whimsical “soap opera” footsteps, the film is devastating in a visceral, palpable way, delving into the upsetting subject matter that the series often had to skirt due to its televised nature. Despite that, it’s still signature Lynch, and you can tell this is a world full of characters he truly cares about. It doesn’t only expand on the disturbing origins of the Laura Palmer murder that the series centers on, but introduces a host of new players into the Twin Peaks universe, including FBI Agents Chester Desmond (Chris Isaak) and Sam Stanley (Kiefer Sutherland), trailer park owner Carl Rodd (Harry Dean Stanton), the mysterious Phillip Jeffries (David Bowie), and the malevolent Woodsmen (the representative of which is played here by renowned German actor Jürgen Prochnow). Ray Wise is incredible here as the tortured Leland Palmer, but Sheryl Lee is the real standout: when you think about the fact that she was originally hired to exclusively exist in corpse and photographic form, it sharpens the perspective on just how incredible her work is here. She brings a heartbreaking depth to Laura Palmer, one that stretches beyond the supernatural forces at play in the demented worlds that surround Twin Peaks. Though it was not received well upon release, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me is a masterpiece, albeit an incredibly sad one.

2. The Straight Story

How David Lynch, a man barely into his fifties at the time, so perfectly encapsulated the determination and persistence of aging with The Straight Story (one of only two of his films based on true events) is something that will continue to astound me. His ability to think and consider outside of his own life and experiences served him well many times, but never better than it did in The Straight Story, his last film of the 20th century. Remembered by many as the “David Lynch Disney movie,” it follows retired farmer Alvin Straight (played by Richard Farnsworth in his last film role before his passing in 2000), who sets off on an interstate journey on his lawnmower to visit his estranged brother Lyle (Harry Dean Stanton) after the latter suffers a stroke. Along the way, Alvin encounters kindly townsfolk, hysterical drivers, and many other colorful characters. Like #1 on my list, The Straight Story has been referred to as “Lynch-lite,” but no one else could have captured this sobering and heartwarming tale in quite the same way. Throw in Lynch collaborator Angelo Badalamenti (who I somehow have not mentioned yet, despite his incomparable contributions to the auditory iconography of Lynch’s projects) delivering his best score yet, and you have yet another masterclass in intentional, methodical, primarily visual storytelling. Very few filmmakers could craft as effective a story as Alvin Straight’s in their lifetime, and Lynch did it far before his time. If that isn’t the sign of a true master, I don’t know what is.

- The Elephant Man

Unapologetically human, The Elephant Man (Lynch’s second feature, which some might call his most “normal” film) cements the director’s fascination with the outsider and the unknown. Anthony Hopkins and John Hurt are at the center of the overwhelmingly empathetic tale of John Merrick (Joseph Merrick in real life), an English man paraded around circuses and freak shows for his severe physical deformities. Merrick is an intelligent and kind man who is feared and misunderstood because of his appearance, and Lynch’s interpretation of his story is touching and unsurprisingly compassionate. Lynch is one of the most discussed and analyzed filmmakers of his time, but like so much of his work, a gorgeous and nakedly emotional piece of art as The Elephant Man must be felt. It’s all about feeling and understanding and love, because what is a world without love? It’s a world that David Lynch did not want to live in, and through his stories about the endurance of love and kindness, we can remember why we are here. To be human is to love, and there’s no better way to tell the story of a man who loved despite everything than with an optimistic outlook on the promising nature of humanity.

If you are interested in more of Lynch’s work, I would also recommend checking out the documentary David Lynch: The Art Life, in which the artist discusses his early history and non-film works. His many short films, internet videos, music, and visual art are available for viewing in various corners of the world wide web.

Leave a comment