The Academy Award for Best Picture has been, under a few different names, awarded for almost a century to the film deemed to represent not necessarily the most popular, but the most culturally relevant in that year’s cinematic lineup. Because of the ever-changing nature of the world we live in, which has only been exacerbated in the last 250 years by the unstoppable force of modern technology, the meaning of that cultural relevance has shifted, which only makes it more interesting to examine the Best Picture winners from the past 97 years. Today, I will start counting down my personal ranking of every Best Picture winner throughout Academy history, starting with…

97. Crash (2005)

Crash is not the worst Best Picture winner in terms of production value; it’s also not the worst because of its performances. Nor is it the worst because of its sound, cinematography, or any of the various below-the-line categories that the Academy awards every year…no, Crash is by far the worst winner because of what it is and what it stands for. A passion project for writer/director Paul Haggis, Crash is an anthology film that depicts escalating racial and social pressure in mid-2000s Los Angeles. Unfortunately, it’s riddled with clichés, narratively and character-wise – a story like this could be incredibly impactful if it approached its themes from the unvarnished perspective of the marginalized people it depicts. Instead, it’s a project spearheaded by an aimless white guy, someone who clearly doesn’t understand that a story on race relations can be done without perpetuating harmful stereotypes that have been infecting society for centuries. It’s miserable and embarrassing, but (and this is the only thing I will give the movie actual credit for) it’s never boring. There’s always something insanely misguided happening from scene to scene, especially considering that those scenes are so short that the moments are never allowed to breathe; the gargantuan amount of characters makes it so that we don’t get to know any of them too well, and they’re reduced to archetypes, which ultimately hurts the story but is great for the sole entertainment value this woefully deluded movie offers. History doesn’t repeat, but it does rhyme. We had Crash 20 years ago, and now we have Emilia Pérez – both are films that claim to be the be-all-end-all totem of representation for a marginalized community that doesn’t often see itself recognized in award favorites, but neither approach that representation with any tact or empathy whatsoever.

96. Cimarron (1931)

An expansive Western epic, and the first of four Westerns to win Best Picture, Cimarron really shows its age – it’s a slog, a dull bore that proves brilliant and captivating older films were not as rampant as the history books would have us believe. The story centers around Yancey Cravat (Richard Dix), a multi-hyphenate journeyman who becomes a prominent citizen in a boom town during the Oklahoma land rush. It’s achingly slow, frequently begging to pick up speed before being once again handicapped by one of its lead characters taking the most basic, least interesting path in pursuit of their so-called “arcs.” Not to mention the sound quality, which is atrocious (though I’ll be a little more lenient about that because of its age). In the pantheon of Oscar winners, Cimarron is definitely one to skip.

95. The Broadway Melody (1929)

The second-ever winner (back when the award was called “Outstanding Picture”) and the first sound film to take home the gold, The Broadway Melody is first and foremost a time capsule, and not a very interesting one at that. Ostensibly, it’s a musical romance, but it feels much more like a revue – much like The Jazz Singer in 1927, the power of sound is at the forefront, and especially when viewed in a modern context, it has become abundantly clear that The Broadway Melody is not much more than a showcase for this revolutionary new technology. The characters sing the same song – the titular “Broadway Melody” – over and over again, and there’s not much variety or narrative diversity when it comes to the central romance. Still, it has cemented its place in cinematic history with its Best Picture win, so it looks like it had the last laugh.

94. Out of Africa (1985)

A perfect encapsulation of what has become known as “Oscar bait,” this epic romance somehow manages to be neither epic nor romantic. It lacks a sweeping love story to anchor it (though there is a love story, it’s not particularly engaging), and is so dreadfully long that it seems to go to insufferable lengths to keep going despite an evident lack of forward momentum. Meryl Streep and Robert Redford are both very good (as they always are), but the only place where Out of Africa truly flourishes is in its landscape photography. Director Sydney Pollack captures the African plains in such a way unparalleled until Planet Earth, and, as contributor Heath Lynch described in his review, it’s an “every frame a painting” type of movie. Alas, it’s not very engaging when it comes to frivolous things like story and character development.

93. Chariots of Fire (1981)

Everyone knows the theme song to Chariots of Fire, but modern awareness of the movie doesn’t go much further than those few iconic notes. It’s based on a true story, following the parallel journeys of Eric Liddell (Ian Charleson), a Scottish Christian, and Harold Abrahams (Ben Cross), an English Jew, as they both compete in the 1924 Olympics for very different reasons. This film is a largely uninspired history-based trek through trite subject matter that doesn’t have much to offer beyond broad social commentary about the religiously divided UK of the early 20th century, but is also notable for containing the uncredited screen debuts of both Kenneth Branagh and Stephen Fry!

92. Around the World in 80 Days (1956)

This three-hour “epic” based on the eponymous Jules Verne novel is pure antiquated drivel. There’s no use beating around the bush – Around the World in 80 Days knowingly perpetuates awful racial stereotypes, and while it isn’t nearly as offensively bad as Crash, it’s not exactly easily forgivable. Set in 1872, the film features David Niven (star of the oft-overlooked A Matter of Life and Death) as Phileas Fogg, an English gentleman who makes a bold and expensive bet that is nothing less than laughable over 150 years later – that he can traverse the entire world in 80 days. What follows is a painfully slow adventure that could easily fit in a two-hour window, in which many easily solvable conflicts are stretched out to absurd lengths, and Shirley MacLaine (who starred in this movie almost 70 years ago, and is still alive!) as an Indian princess. What merits it does have are largely limited to a gorgeous animated opening credits sequence, which, like much of the film, drastically overstays its welcome.

91. Tom Jones (1963)

Tom Jones is one of those Best Picture winners that makes it hard to believe a film like this could possibly win that award. It’s deeply strange, but I will give it props that it fully commits to being deeply strange. It’s based on the 1749 novel The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling (probably best to shorten that title), and stars Albert Finney as the titular foundling, who falls in love with his neighbor Sophie Western (Susannah York) and becomes caught up in a heritage plot that threatens to destroy both his livelihood and every relationship he had. The film moves at a breakneck pace and almost has a musical quality to it, despite primarily being an offbeat comedy. It’s chaotic and weird…not something I would ever choose to rewatch, but nowhere near unwatchable.

90. The English Patient (1996)

Another epic that cherry-picks its events to portray its subjects in the most palatable light – at least The English Patient notes in its end credits that it is indeed a “highly fictionalized” account of the life of László Almásy, played by Ralph Fiennes, though it plays more like a sensationalized romance than a historical drama with something to say. Its structure is interesting, though, and the performances are decent (Oscar-worthy? I’m not sure), especially those from Willem Dafoe, Julianne Binoche, Colin Firth, and Jürgen Prochnow. This film has the reputation of being an annoyingly overlong drama with very little substance, and I’d say that still holds true. But it’s a real shame – like Out of Africa, there’s a lot of beauty to look at, but the film’s core fails to live up to its vision.

89. Gigi (1958)

Gigi, an incredibly French Technicolor musical about grooming disguised as young love, begins and ends with an old man singing the tune titled “Thank Heaven for Little Girls” while staring straight down the barrel of the lens. You can’t make this up. Like many of these bottom-tier Best Picture winners, there’s a lot to admire visually, but I found Gigi to not only be achingly slow, but it’s also a film with woefully misplaced priorities. Set about half a century before its release, the film can’t seem to decide on how it wants to portray its central romance – is it sweet? Is it strange? How are we, the audience, supposed to interpret what we’re seeing? It’s that confusion that hampers Gigi, and knocks it down from a worthwhile award winner to a bewildering mess.

88. Cavalcade (1933)

I’m dead serious when I say that Cavalcade is the proto-Forrest Gump. Set throughout the first third of the 20th century (from New Year’s Eve 1899 to New Year’s Day 1933), the film is told from the perspective of a proper English family, the Marryots, and their interactions with the history of their time. We are taken through their lives as they are affected by the death of Queen Victoria, the Titanic disaster, and World War I, among many others. Sometimes, those connections sneak up on you (the Titanic scene features an especially, and certainly hilariously unintentionally, reveal), but more often than not, we’re stuck with stuffy, bland, well-to-do English characters that don’t have much individual merit. The concept is an interesting one, and there are flashes of brilliance, but I still can’t believe this is a Noël Coward script (albeit an adapted one). It manages to mostly be incredibly dull, while also not fully exploring the relationships between its many characters, all of whom are brought to life by overwrought theatre performers. It also acts as a fascinating time capsule as a historical film that is now itself a piece of history, cemented by its (questionable) Best Picture win.

87. Going My Way (1944)

World War II was raging strong, and as far as the American public knew, it was nowhere near the end. It only makes sense that, for Best Picture that year, the Academy would vote for a more uplifting story, one that barely touched the larger world issues they would rather ignore. Enter Going My Way, a relatively straightforward drama starring Bing Crosby as Father Chuck O’Malley, an enthusiastic young priest appointed to salvage a New York parish after its numbers continue to dwindle. O’Malley connects with the local youth, inspires an aspiring singer, and eventually wins over the cranky, older Father Fitzgibbon (played by Barry Fitzgerald, who won an Oscar for his role here alongside Crosby). You’ve seen this story a thousand times before (most recently, and successfully, in Apple TV’s Ted Lasso), and it’s nothing more than positivity propaganda – but there is plenty of merit to its individual existence. It just doesn’t stack up very well against most other winners of the award.

86. Dances with Wolves (1990)

(In)famous for beating Scorsese’s Goodfellas for Best Picture, Dances with Wolves is both the beginning and end of an era. It kicked off Kevin Costner’s directing career, and, like Unforgiven, bridges the gap between different eras of the Western’s reign over the interest of the moviegoing public. Dances has been discussed for decades, ever since its win, and there’s not much to be said that hasn’t already been vocalized; Costner is not exactly the dynamic leading man one would expect from a story like this (I can see that working for some people, but it most definitely doesn’t for me), and it’s hard to miss the clear “white savior”-ness of it all, even though Costner’s take on the story is far less offensive than some of its contemporaries. On the other hand, it’s a stunning landscape spectacle, and the supporting performances are filled with strength and conviction, a notable antithesis to Costner’s. All that is to say that it won enough awards in its day that it must’ve resonated with a fair amount of people. Unfortunately, I am not one of them.

85. The Great Ziegfeld (1936)

Florenz Ziegfeld Jr. was arguably the most noted theatre impresario of the 21st century, in a time when Broadway and theatre had to prove their worth amidst the rise of the motion pictures arts. This three-hour tribute, itself a loose adaptation of the revue Ziegfeld Follies, is a sanitized retelling of Ziegfeld’s life…but mostly the bits that reflect well on his legacy. It’s hollow and a little shallow, but the musical numbers are nothing short of spectacular; for better or for worse, it’s like watching a large-scale Broadway show, with repetitive segue scenes to get us from musical number to musical number. I did not necessarily find The Great Ziegfeld to be dull, but (like The Broadway Melody) it’s less of a movie and more of a theatrical production, a meld of the two mediums that is not as successful as many others have been in the last century.

84. Driving Miss Daisy (1989)

Infamous for its shiny glorification of self-congratulatory interpersonal race relations that has continued to the present day (see: Green Book), Driving Miss Daisy is less offensive than one might expect on the surface, but it’s still very much a product of its time. Morgan Freeman (who reprised his role from the original off-Broadway stage production on which the film was based) and Jessica Tandy are both very good, but the underlying shadow of this film’s all-too-casual depiction of its subject matter will always eclipse its self-evident charm and good humor. There’s good intention here, but it’s unfortunately very misplaced.

83. Gentleman’s Agreement (1947)

Gregory Peck stars as the impeccably-named Philip Schuyler Green, a freelance journalist who is asked by a magazine publisher to write an article on the persecution of the Jewish people. While not being Jewish himself, Green takes on the assignment and goes “undercover,” posing as a Jew to expose the rife societal evils of antisemitism. Elia Kazan’s dialogue-driven drama feels very much like a reaction to the global events of the past decade of its release – after all, World War II had only ended two years previously, and antisemitism was still on the minds of many. Sometimes, it even veers too heavy-handedly in that direction, but there’s certainly nothing wrong with that – these are themes that resonate just as much now as they did almost 80 years ago. This film is also notable for featuring an early screen appearance (and a very good performance to boot) by Dean Stockwell, who plays Green’s son, Tommy.

82. Rain Man (1988)

Everybody loves Rain Man, and I wish I did, too. Tom Cruise playing against type, Dustin Hoffman straying outside of his comfort zone, one of Hans Zimmer’s first-ever Hollywood scores…it should be an easy recipe for daring success. And while it’s true that Rain Man certainly has charm to spare (courtesy of the Barrys: director Levinson and writer Morrow), I found it to be a somewhat hollow and (in a bizarre trend that several other Best Picture winners end up following) sensationalizing of neurodivergence in a markedly uncomfortable way. It’s interesting, though, to see how far Best Picture winners have come in terms of omnipresent cultural relevance – while films like Everything Everywhere All At Once and Anora are popular, that’s primarily within film circles, with some outreach into the mainstream. In the 80s, if you didn’t see the sensation that was Rain Man, you were missing out on the cultural conversation. You weren’t “cool.” That hasn’t been the case for Best Picture in many years now (with some Oppenheimer-sized exceptions, of course).

81. Oliver! (1968)

My brother starred in a regional theatre production of Oliver! many years ago, and it was around that time I saw Carol Reed’s feature adaptation for the first time. As befits a stage-to-film translation, Oliver! is quite long, clocking in at over two and a half hours, but it’s an incredibly faithful adaptation of both the stage show and Dickens’ original text. Stylistically, it’s impeccable, providing a filmic transportation to Victorian England, but it’s mostly bogged down by a firm commitment to the theatrical pacing of the show, which doesn’t play as well on-screen.

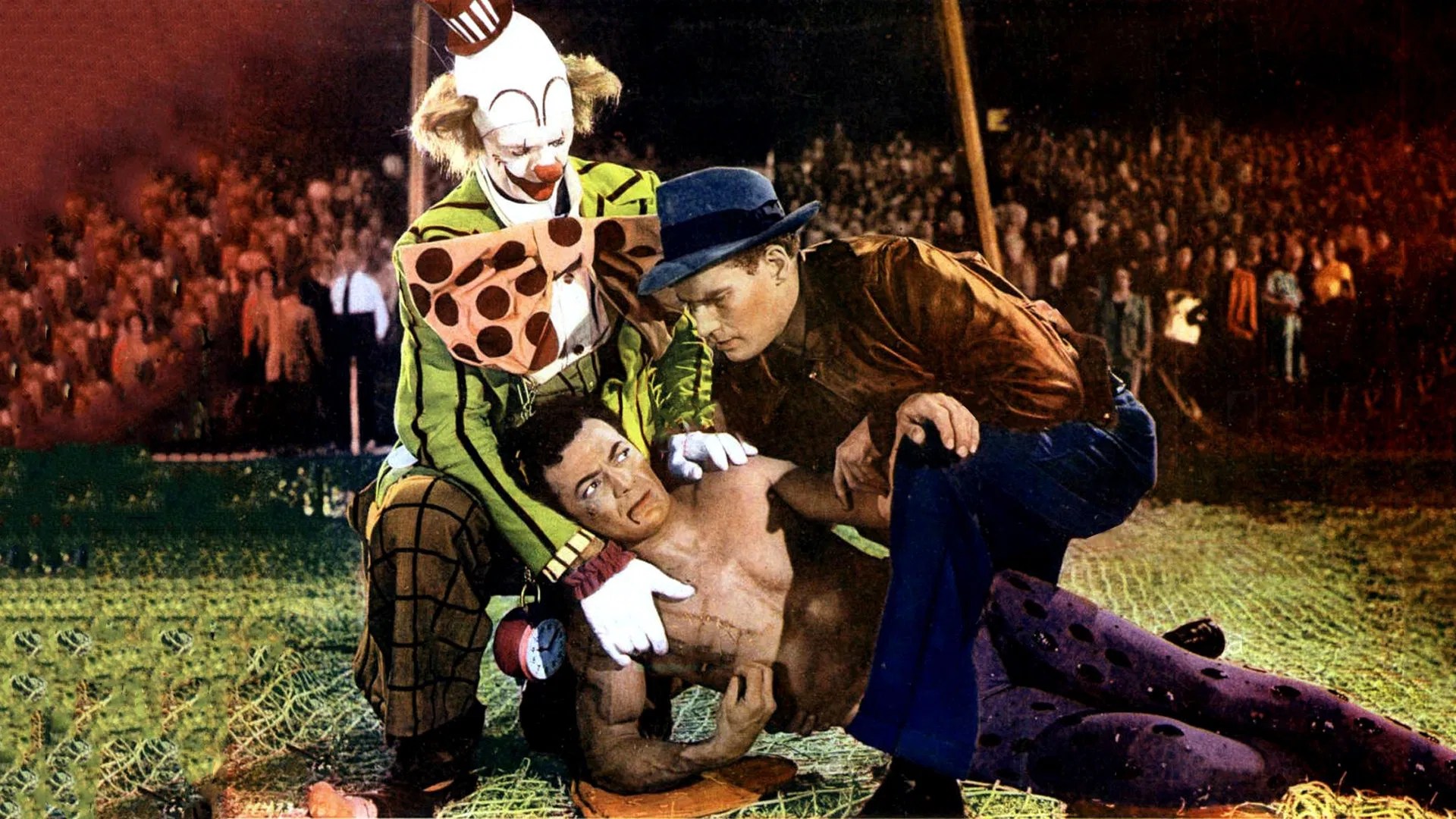

80. The Greatest Show on Earth (1952)

The circus epic that inspired Steven Spielberg, The Greatest Show on Earth is an ensemble piece from Cecil B. DeMille, a famed pioneer of early cinema. First and foremost, it’s a film about spectacle, and it has plenty of it; in fact, at times, it seems like DeMille was more interested in the breathtaking circus performances than he was in any of his characters, most of whom are reduced to archetypes and underdeveloped throughout its over two-and-a-half hour runtime. It’s perhaps best-known for its bombastic train crash sequence, which was both a marvel of contemporary special effects and the pinnacle of the film’s emphasis on spectacle. I found this film to be a memorable experience, but its economy of storytelling and visual priorities do not necessarily stand the test of time.

79. An American in Paris (1951)

I’ll let you in on a little secret here: most of the Best Picture winners are good. I know, I know, it’s hard to believe! But here, with An American in Paris, we are entering the zone containing the “good, not great” of the bunch – movies that more than warrant the cultural praise, but ones I often found difficulty in connecting with. Like All That Jazz, An American in Paris has an undeniable, dynamite final sequence that leaves its audience with a memorable, fuzzy feeling, but apart from that, there’s not much to it; it’s another MGM Technicolor musical with largely unmemorable songs and numbers. It’s the talent that sets it apart; Gene Kelly stars as American expatriate Jerry Mulligan, who reconnects with old friends and finds himself amidst a web of romantic drama while trying to establish his own reputation as a painter. It was intriguing to see director Vincente Minnelli’s first collaboration with young actress Leslie Caron (who later went on to play the titular role in Minnelli’s Gigi), and Kelly is always a delight, but I wasn’t as enraptured by An American in Paris as much as I hoped…until the final 15 minutes. Then, you can’t look away…and while some may say how you open your movie is more important than how you end it, I firmly believe the opposite. Kelly’s ballet is nothing short of spellbinding, and I’ll be damned if it didn’t make me excited to see more of his work.

78. From Here to Eternity (1953)

I’ll be very clear – Fred Zinnemann’s mid-century Best Picture winner primarily takes place at a U.S. Navy base in Hawaii in 1941. Somehow, throughout the entire film, which features a series of intertwining dramatic tales of the base’s residents, I completely forgot about the world-shattering event that took place at a U.S. Navy base in Hawaii at the end of 1941. It’s not too much of a spoiler to say that the film ends with an incredibly gripping extended sequence that depicts the bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japanese fighters that drew the United States into World War II, but it definitely caught me (and the film’s characters) by surprise. Each storyline up until that point is brutally interrupted, just as life was interrupted in the 1940s when the war broke out, and the film captures that jarring feeling very well. Zinnemann’s quiet epic signals a willingness on the part of the culture to finally tell stories about our nation’s role in the War (excepting previous Best Picture winner The Best Years of Our Lives, which specifically tackles post-War life), a willingness that has continued in the awards roster to this day.

77. Grand Hotel (1932)

The White Lotus of its day (in more ways than one), Edmund Goulding’s Grand Hotel is a real “who’s who” of Old Hollywood stardom – Greta Garbo, John Barrymore, Joan Crawford, Wallace Beery, Lionel Barrymore, and Jean Hersholt are just some of the recognizable names populating this all-star cast, which finds itself intermingling at the titular Grand Hotel in Berlin less than 15 years after the end of the Great War. Doctor Otternschlag (Lewis Stone) brings us into the scene, introducing the film in the hotel’s lobby, saying that it’s “always the same…people come. People go. Nothing ever happens.” It might be hard to believe, but a lot happens in this movie! Lines are crossed, relationships are forged and betrayed, and a general atmosphere of intrigue permeates every moment. Grand Hotel feels dated, but not in an unpleasant way – it spotlights just how interesting it is, when delving into the Best Picture archives, what was considered “unmissable” cinema of the time. Grand Hotel has aged well in that regard, standing out from other contemporaries like The Broadway Melody and Cavalcade.

76. Nomadland (2021)

It won’t ruffle any feathers to say that 2020 was a bizarre year. Many of us sheltered in place for months on end, some continued their essential work, and the film industry ground to a halt. Nomadland premiered at various festivals that fall before winning big at the Oscars – and why not? It only makes sense that a movie about the constantly transitory nature of life would be at the forefront of the cultural consciousness in a year that only further proved its thematic structure as resonant as ever. Frances McDormand stars as Fern, a widow who abandons her stationary life in favor of a nomadic, cross-country lifestyle. Many real people appear as themselves, which lends the film an even more authentic feel, something crucial to its very soul. Even though it’s her third film, Nomadland also marks writer/director Chloé Zhao’s mainstream breakthrough, a declaration of stylistic intent that carries through her entire filmography (yes, even Eternals).

75. The Life of Emile Zola (1937)

The second biographical film to win Best Picture, The Life of Emile Zola stars Paul Muni as the revered French author (whose existence I was unaware of before watching the film) as we follow him from his defiant rise to fame through his involvement with the Dreyfus affair (a historical event, you might not be surprised to learn, I had not heard of before watching the film). Oftentimes, biopics take generous liberties while portraying the life of their subject, sacrificing full accuracy for a more enhanced silver-screen experience. The Life of Emile Zola, however, despite omitting some cultural context involving antisemitism in France during Zola’s life (as of the film’s release, the Nazi Party had recently gained total power in Germany), I learned a lot about not only Zola, but the conditions in Europe in the mid-19th century that allowed corruption and injustice (that led to instances like the Dreyfus affair) to run unchecked through the bureaucracy. It’s a noteworthy historical text, and it works very well as a piece of entertainment as well.

74. Hamlet (1948)

Believe it or not, I had never read Hamlet before watching this big-screen adaptation for the first time, nor had I ever seen a staged production. I was aware of much of the story through cultural osmosis, but for all intents and purposes, Sir Laurence Olivier’s abbreviated adaptation of Shakespeare’s tragic masterpiece was my first experience with the Prince of Denmark. Olivier’s screen version, which he adapted, directed, and starred in, plays out much like a stage performance, cinematic yet extremely methodical – it’s very clear that every performer is much more accustomed to the theatricality required by being on stage, but for the most part, that theatricality translates very well. Hamlet is also notable for being the first British film to win Best Picture, and was quite controversial among Shakespeare purists, who criticized Olivier’s cuts – but as fans of cinema are well aware, oftentimes cuts are necessary for a stage production to make the full leap to the big screen (don’t tell Kenneth Branagh, though). Next up – Hamlet on stage.

73. A Beautiful Mind (2001)

A box office smash and a critical favorite, Ron Howard’s A Beautiful Mind (the second of two consecutive Best Picture winners starring Russell Crowe) is a tragic tale that lives up to the promise its title makes – it’s a portrait of a truly beautiful mind, specifically that of John Nash, a real-life mathematician whose works became a fundamental aspect of what we now know as game theory, in addition to a number of other accomplishments. Crowe plays the character sensitively and with great care, but the film seems more intent on sensationalizing Nash’s paranoid schizophrenia and exaggerating it to frustratingly fictional degrees, sidelining his true accomplishments and legacy in favor of contrived drama. As it stands, though, it’s a very competently-produced film, with an excellent supporting cast and a skillful grasp of dramatic tension…it just doesn’t quite succeed as the elevated humanistic drama slot that films like The Imitation Game ended up becoming.

72. Mrs. Miniver (1942)

Speaking of wartime dramas, here we go! Since there was, at the time, no American war stories to be told, we had to make do with Mrs. Miniver, a domestic drama about a family whose lives are inexorably changed by the advent of the Second World War. At the time when most of its scenes were filmed, the US hadn’t yet joined the war (though some scenes were reshot to more accurately reflect the international attitude towards certain German characters), so the film remains a strange midpoint…there were no heroic war stories to be told by Americans, so the quiet rebellion of housewife Kay Minivier (Greer Garson) would have to do. Mrs. Miniver share some similarities with Cavalcade, in the sense that it’s centered around the lives of ordinary people during a time of great change in the world, but it’s superior to the latter in nearly every sense of the word; for one, the characters of Mrs. Miniver (including Kay’s husband Clem, their son Vin, and his love interest Carol) are much more sympathetic and interesting, and their familial drama is treated appropriately when put up against the gargantuan stakes of the War. As a film, Mrs. Miniver is engaging, but as a historical text, it’s gripping.

71. Million Dollar Baby (2004)

It was only a matter of time before Clint Eastwood won Best Picture again. He had revolutionized the genre where he had made his name with the western Unforgiven, and been lauded for it, and years later, as he settled into the final phase of his career (that of the mid-budget, real-world human drama), it only made sense that he’d direct a film perfectly tailored to the Academy’s sensibilities: an underdog sports movie about believing in yourself and defying the odds, with some of the world’s biggest stars (and a few rising ones) attached to the cast. Eastwood stars, of course, alongside Hilary Swank, Morgan Freeman, and Jay Baruchel, among others – and the cast is fantastic. They’re certainly not the issue I have with the movie…in fact, the issue is largely a matter of taste. I have never enjoyed playing or watching sports, and “sports” as a genre has never particularly interested me. Movies like Challengers and A League of Their Own rise above by virtue of their multi-genre sensibilities, so even though Million Dollar Baby is a technically proficient film, it is never one I will actively choose to ever revisit.

70. Gone with the Wind (1939)

Known as one of the greatest films ever made, Victor Fleming’s three-and-a-half-hour epic is known for many things – as one of the longest must-see classics, for its central romances, for its iconic lines (“Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn”)…but its legacy was cemented very quickly upon its release. It overcame numerous delays and production troubles, and post-production wrapped up just a month before its premiere in December 1939. It was an unprecedented box office success, and currently holds the record for the highest-grossing film of all time (provided you adjust for inflation), clocking in with an astounding $4.3 billion in today’s dollars. Vivien Leigh and Clark Gable star as romantic interests Scarlett O’Hara and Rhett Butler, who spend the film’s 3+ hours in a roundabout “will they, won’t they” entanglement which, of course, ends in their marriage. Gone with the Wind had a big presence at the twelfth Oscars ceremony, winning ten (including two honorary awards) from thirteen nominations, which included Hattie McDaniel’s historic win as the first African-American to win an Academy Award.

69. A Man for All Seasons (1966)

Playwright Robert Bolt adapted his own play for the screen about a lesser-known, yet still crucial, aspect of English history, and in one of the most interesting Best Picture wins of the mid-20th century, it won some of the biggest prizes at that year’s Oscars. Nowadays, a stuffy historical drama is an all-too-clichéd pick to win that big, but in a decade of revelatory genre pictures, a quieter, dialogue-driven tale doesn’t exactly fit in as well. Paul Scofield stars as Sir Thomas More (a role he originated on the West End), the Lord Chancellor of England during the reign of the infamous Henry VIII. More refused to endorse the annulment of Henry’s marriage to Catharine of Aragon and to take an oath declaring Henry the Supreme Head of the Church of England, two defiances that made him into a major political target. Fred Zinnemann, who also directed From Here to Eternity, is behind the camera, and among the film’s supporting players are Orson Welles, Vanessa Redgrave, Susannah York, and a very young John Hurt, as well as an incredibly memorable appearance by Robert Shaw as King Henry VIII. A Man for All Seasons is compelling cinema, buoyed by its cast and, honestly, its educational value. Learning things is a lot more fun when it’s packaged inside commercial entertainment!

68. The Last Emperor (1987)

The Last Emperor is a bizarre international convergence, the likes of which have become much more common as Hollywood has expanded across the globe. This Best Picture winner is an American epic, filmed in China, helmed by an Italian director…and just on that basis, The Last Emperor is a bit of a culture clash, balancing different aesthetics and sensibilities carried across the oceans many times over. It’s a paradox of portrayal with the potential to either enhance or diminish the efficacy of its subject’s story, and while the film is not entirely successful, it feels appropriately epic, spanning six decades in the life of Puyi, whose reign became a contentious point in the unsteady global politics of the early 20th century. John Lone turns in an impressive performance as the older Puyi, trapped as a political prisoner in an internment camp after the Soviet invasion of Manchuria and forced to reflect on his turbulent life. It’s heartbreaking and achingly beautiful at times, and director Bernardo Bertolucci’s unprecedented production access to China’s Forbidden City lends the film a crucial legitimacy that elevates it above your standard biopic.

67. The Best Years of Our Lives (1946)

Nightmarish irony dominates William Wyler’s postwar drama that follows three veterans upon their return from fighting in the Second World War. It’s by far the earliest high-profile film to tackle the complexities of soldiers returning from war, especially after a conflict as early in cinematic history as World War II, and Wyler’s examination of PTSD and shifting social dynamics in the mid-20th century is emotionally devastating as well as chillingly prescient about the bleak future of veteran affairs in our country. Its best performance is given by Harold Russell, a real war veteran who lost both of his hands in World War II before being cast in Wyler’s film; the hooks given to him as a replacement are central to his character’s arc, and he is responsible for the film’s most devastating moments. Russell won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor, but he was also given an honorary Academy Award in the same year, marking the first and only time that the Academy gave two awards for a single performance.

To Be Continued!

Leave a comment