Welcome to class! My full-time job is working at a university, and I teach as well. One of my dreams has always been to teach a film class. Taking students through the world of cinema and helping them learn about the art form that I am so passionate about would be an amazing experience. But alas…I teach math. This series, “Lessons from the Wasteland,” is my opportunity to offer readers a curated watchlist to learn through doing (…watching movies). Each film on this list will highlight a filmmaker, sub-genre, filmmaking technique, or significant topic in order to broaden your cinematic horizons. For this month, we have…

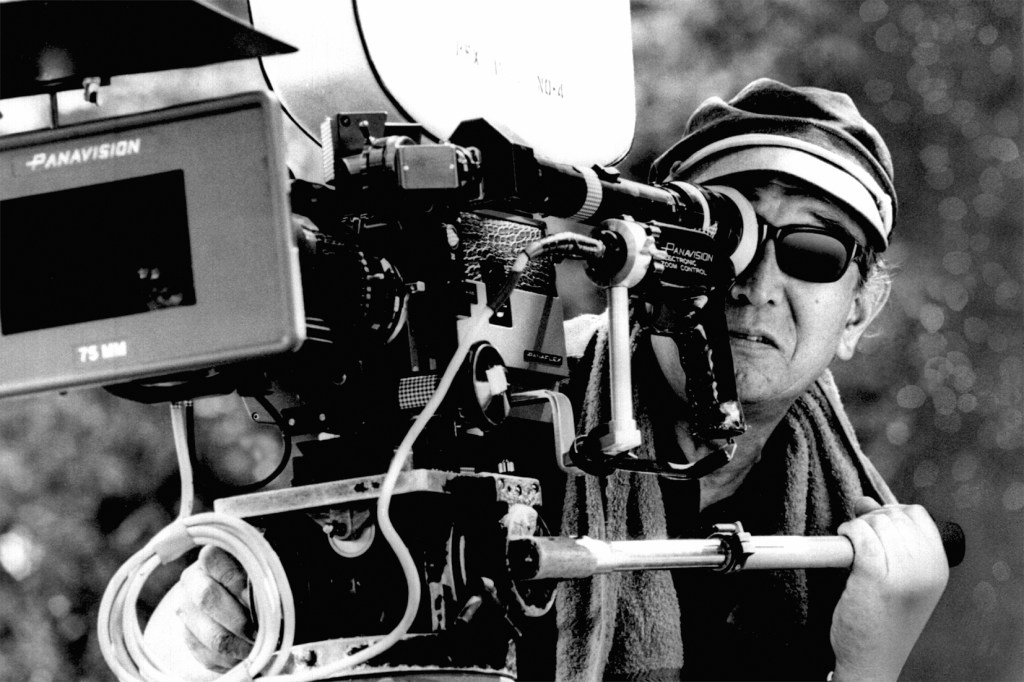

Akira Kurosawa

Rashomon (1950)

Kurosawa made plenty of samurai films, but few of them are as dynamic as Rashomon. First off, there are few Kurosawa films with such a complex and layered narrative as the one here. Many films since this one have adopted the storytelling approach of giving a variety of perspectives on the same events. This is such a compelling exploration of themes like perspective and the faulty nature of human memory. When a film can balance this idea well, it opens the door for an experience that is challenging and compelling for the audience. Kurosawa delivered arguably the greatest example of such a narrative with his samurai film Rashomon.

The way the narrative is framed builds plenty of tension, suspense, and mystery. Rashomon focuses on the rape of a bride and the murder of her samurai husband, but that seems so final and decided, which is exactly what Kurosawa avoids with his approach to the story. We hear about (and see) these events through the perspective of the accused bandit, the bride, the samurai’s ghost through a medium, and finally, a witness (the woodcutter). This film is less than 90 minutes, but it packs so many layers into it and challenges the audience. Obviously, each approach to the story paints a different picture. What is the truth? Are any of them the truth? That is the point. Every human being has a perspective, which is guided by their worldview, biases, and the actual elements that they see. Kurosawa explores this uncertainty in such a compelling and layered way. Few films feel so satisfying while bouncing around the truth in such a purposeful manner.

The storytelling elements are only part of the mastery in Rashomon. The performances are layered and incredible. Toshiro Mifune is a force as this dangerous bandit who brings a violence and intensity that is unmatched. Machiko Kyo delivers a variety of layers through the different stories of how this wife, who is rape,d comes to grips with this reality. Takashi Shimura is another legend of Japanese cinema, and delivers such a strong turn as the third-party witness. But Kurosawa is an incredible star of the film, with the impressively crisp and sharp filmmaking on display. The camera feels so inspired and intentionful with Kurosawa’s great eye for cinema anchoring the film. The action of this duel (performed multiple times) is so visceral and compelling with its various presentations.

Ikiru (1952)

Where are the samurai?! Kurosawa’s filmography has largely been pigeonholed in general culture. Scorsese does not just make gangster films, and Kurosawa does not just make samurai films. There is so much depth in Kurosawa’s filmography, and you can find some impressive films that capture so much drama in a modern context. Ikiru is one such masterful effort from a whole new perspective that Kurosawa delivered on.

This is a film of the modern mundane. The protagonist is a bureaucrat. His mission is to make a park. This feels so simple and ordinary…but nothing is ordinary in the hands of Kurosawa. That is especially true when you have a legend like Takashi Shimura leading the way with such an iconic and deeply affecting performance. Ikiru is a story of a man who has wasted away in a life stuck in the muck, and now is given a ticking clock to reckon with: fatal illness. What would you do if you found out you were going to die soon, and you had not done much with your life up until that point? That is the journey that Shimura explores through this meaty role. Spiraling out of control, we see a vulnerability and sadness surrounding Shimura’s performance like a tidal wave of regret and apathy. Shimura balances the necessary empathy to keep the audience invested, along with a shame that engulfs this spiralling and desperate man.

The story is engrossing, compelling, and harrowing as we see this man falling to pieces. But the twist of this tale is that man is able to accomplish one lasting thing of value before he slips from this moral coil. Kurosawa chooses to tell this story in a nonlinear fashion, as we witness this man’s funeral and what he was able to actually accomplish only through his peers and strangers. This is such a bold and affecting choice that it tricks the audience into sensing that Kanji Watanabe’s life ended without resolution. But the third act sees Shimura breathe new life into Kanji, as he weathers the tumultuous waves and gusts of the unbearing storm that is bureaucracy. We see Kanji’s resolve as he overcomes his fate and spiraling emotions to accomplish something and leave a modest yet meaningful legacy. The beautiful sequence of Kanji in that park at night stands out in one of Kurosawa’s least dynamic films. The stark night sky, the snow, and the emotional turn by Shimura make it all possible and deliver something so satisfying.

Seven Samurai

Kurosawa showed the amazing capability of cinema with his three-and-a-half-hour action masterpiece in the form of Seven Samurai. It’s his quintessential samurai film that delivers an experience that is so towering and impactful. Each of these seven central characters has so much personality, definition, and depth to go around. There is a cool range of different warriors from the wise and experienced leader (Takashi Shimura) to the wild and unhinged young upstart (Toshiro Mifune). All seven of them stand out in their own way, from both a personality and warrior perspective. Kurosawa is not afraid to deliver real stakes, as not all of these warriors will make it out alive. When you need that weight, you’d better make sure that each of them feels like a real person whom the audience can invest in. That is exactly what Kurosawa accomplishes.

This legendary filmmaker also doesn’t shy away from complexities in his sprawling story. You have the conflict at the heart of the film, where a gang of bandits strong-arms this small village. Desperate and outmatched, the town elders seek out ronin for hire to protect them. But there are other layers to this dynamic, as the townsfolk hide their women and children from the ronin…not the bandits. This lack of trust, culture clash, and classism give Kurosawa’s film intriguing layers that most action flicks would try to avoid.

The levels of moral grey areas match the film’s crisp and gorgeous black-and-white cinematography. But the biggest selling point of Kurosawa’s film has to be the action. The climactic action sequence turns into an all-out war. The conflict is structured in waves with variety, intensity, and creativity. The sword fighting is well-choreographed and well-staged. What Kurosawa is able to accomplish by keeping the intensity, suspense, and energy up for such a prolonged period of time is excellent. This might be one of the best-paced three-and-a-half-hour films of all time, as Kurosawa fills the time with strong character moments, thrilling action, an impactful score, and impressive filmmaking.

High and Low (1963)

There are no samurai to be found in High and Low, but there is plenty of masterclass filmmaking and storytelling. The concept of the film is quite unexpected and challenging: A wealthy shoe factory tycoon (Toshiro Mifune) believes his son to be kidnapped, but it turns out to be (mistakenly) the son of his chauffeur instead. However, the kidnappers still want Mifune’s Kingo Gondo to pay up anyway. What should he do? This moral dilemma is the heart of the film, and creates the tension and suspense that drives this crime thriller forward.

Long before other Asian directors like Bong Joon-ho delivered compelling mysteries, Kurosawa set the tone with this thematically dense and compelling mystery. Outside of the moral quandary, there is another layer to this whole situation. This is all about money and class warfare. This whole thing was staged because the kidnapper is downtrodden and of the lower class. His plan to stick it to this rich man by kidnapping his son is all part of the plan. The mix-up of targets certainly makes the decision murkier, but it still hits the thematic purposes of the kidnappers.

Mifune gives a layered and compelling performance that anchors the whole film. Most of Mifune’s performances are much bigger and higher energy, but he shows his range with this more subdued but equally engaging performance as he reckons with the unfortunate situation he has found himself in. The complexity is deepened by the fact that this money was meant to buy Gondo out of his corporate life to give him control and restore his passion. There is plenty of tension in moments between Gondo and his chauffeur, Gondo and the police, and a great interaction between Gondo and the kidnapper in the later moments of the film.

Kurosawa showed he didn’t need swords to deliver a compelling story. High and Low just needed a powerhouse leading performance, a morality tale, good old-fashioned investigations, and poignant themes to deliver a masterwork of storytelling.

Ran (1985)

Was Kurosawa’s cinematic voice just as successful with the richness of modern color filmmaking? If Ran is any indication, he just might be even better with it.

From a visual standpoint, Ran is a towering achievement of visual storytelling. The richness of colors is quite significant, with the costumes delivering some visual splendor. The battle sequences, including the major castle siege, are breathtaking to look at. The smoke, fire, and makeup all leap off the screen in vivid cinematic bliss. The scale of Ran is also awe-inspiring, with battle sequences involving an insane amount of extras. Kurosawa went big in this later effort, which is no less a masterpiece compared to the rest of the films in this article.

The color cinematography is downright gorgeous, and just might make it one of the most beautiful films ever made. But it is not just the color that makes this so powerful visually. The camera choices are inspired and dynamic. The intimate and uncomfortable close-ups of Tatsuya Nakadai’s Lord Hidetora Ichimonji with his elderly make-up are incredibly striking. The choice to show some more brutal deaths with blood splattering a wall makes for some evocative shots. This just might be the most impressive visual experience in all of Kurosawa’s filmography.

But what makes the film so special does not end there. Nakadai might not be Mifune or Shimura, but he stands out with his powerful, layered, and emotive performance as the aging Lord whose power is sought after by his greedy children. The rest of the cast is quite impressive, too, as they give the film the foundation to allow Nakadai to swing big.

Kurosawa had a penchant for telling dramas full of scale and weight. Unsurprisingly, one of his biggest influences was William Shakespeare. Throne of Blood is an excellent and masterful reimaging of Macbeth in feudal Japan, but Ran is the effort that really sells his knack for Shakespeare’s storytelling. Ran is a towering, gorgeous, and sprawling reimagining of King Lear set in the realm of feudal Japan. Ichimonji is Ran’s King Lear stand-in, desperate to hold onto his power and throne. But like Lear, his children have other plans. This story is massive in scale, but deeply personal in conflict, as a father must contend with his children for power and control of his own home. This is the last true masterpiece of Kurosawa’s illustrious career, but his work will endure forever, and future generations will be enjoying his films for years to come.

Also see: Throne of Blood, Red Beard, Dreams, Yojimbo, The Hidden Fortress

Leave a comment